-

Module 2.0 How to be Successful in this Course

-

Module 2.1 Introduction to Natural Gas

-

Module 2.2 The Natural Gas Industry in British Columbia

- Overview

- Learning Outcomes

- Natural Gas Science – The Simple Version

- Natural Gas Science – Chemistry

- Natural Gas Science – Physics

- Natural Gas Science – Units of Measurement

- Natural Gas Science – Geology

- Natural Gas Resources and Uses

- Oversight of the Natural Gas Industry

- Understanding Land Rights and Natural Gas

- Energy and the Future

-

Module 2.3 Upstream – Well Site Selection, Preparation and Drilling, Completion, Production, Water Recycling, and Reclamation

- Learning Outcomes

- The Upstream Sector – Extraction and Processing

- The Upstream Sector – Exploration and Site Selection

- The Upstream Sector – Preparation and Drilling

- The Upstream Sector – Completion

- The Upstream Sector – Production

- The Upstream Sector – Water Recycling

- The Upstream Sector – Reclamation

- Upstream Companies and Jobs in British Columbia – Companies

- Upstream Companies and Jobs in British Columbia – Industry Associations

- Upstream Companies and Jobs in British Columbia – Professional Associations

- New Vocabulary

-

Module 2.4 Midstream – Transportation, Processing, Refining

- Learning Outcomes

- The Midstream Sector

- The Midstream Sector – Processing Natural Gas

- The Midstream Sector – Liquefied Natural Gas

- The Midstream Sector – An Emerging Industry

- The Midstream Sector – Processing LNG

- The Midstream Sector – Proposed LNG Projects in British Columbia

- Transportation

- Midstream Companies and Jobs in British Columbia

-

Module 2.5 Downstream – Refining and Markets

-

Module 2.6 Health and Wellness in the Natural Gas Industry

-

Module 2.7 Safety

-

Module 2.8 Terminology and Communication

-

Module 2.9 Jobs and Careers

- Learning Outcomes

- Industry Outlook

- Technology is Changing Workforce and Skills

- Employment in the Natural Gas Industry

- Employment in the Natural Gas Industry – Types of Employment

- Employment in the Natural Gas Industry – Range of Jobs

- Employment in the Natural Gas Industry – High Demand Jobs and Occupations

- Occupational Education and Training

-

Module 3.0 How to be a Valued Employee

-

Module 3.1 Identifying Interests and Skills

-

Module 3.2 Looking for Employment in Natural Gas

-

Module 3.3 Applying for Employment in Natural Gas

Natural gas is a fossil fuel, formed from exceptionally large quantities of plant and animal remains that accumulated between layers of sediment on the bottoms of lakes and oceans. Tremendous pressure exerted from the layers of sediment over many millions of years and heat from the earth’s core have converted the organic materials into natural gas.

Primary and Secondary Natural Gas

When organic matter descends far enough into the Earth’s crust and reaches a temperature of 120˚ C, it begins to cook. Eventually the carbon bonds in the organic matter break down and fossil fuels are formed. Natural gas formed in this way is called primary gas.

When oil, once it has formed, continues cooking for millions more years, it too can degenerate into natural gas. This is known as secondary gas.

This implies that the deeper the fossil deposits, the more heat and pressure they are subjected to; and consequently, the more likely there is to be natural gas, instead of oil. Similarly, oil fields are usually accompanied by natural gas deposits.

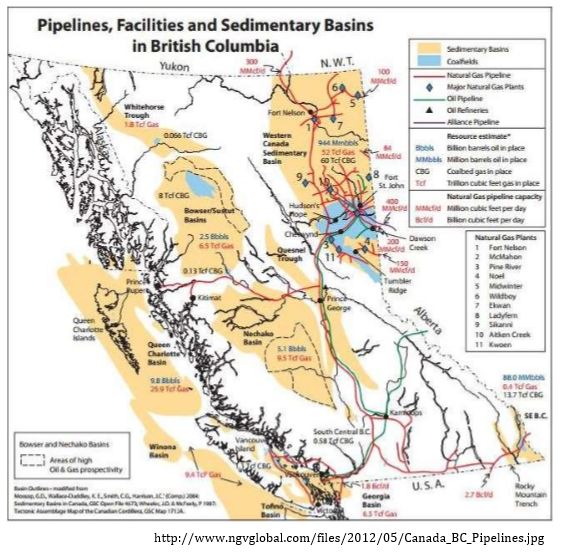

Sedimentary Basins

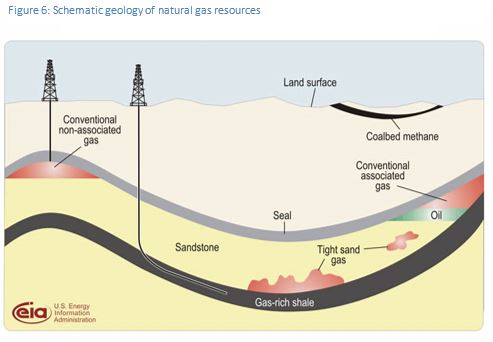

Most natural gas is found in reservoirs deep below the earth’s surface and ocean floors.

Most often, natural gas (alone or together with oil) is found in what are called sedimentary basins.

A sedimentary basin is a depressed area of the earth’s crust where tiny plants and animals once lived or were deposited with mud and silt from streams and rivers. These sediments eventually hardened to form sedimentary rock. Exposure to heat and pressure over millions of years caused the soft parts of plants and animals to gradually change to crude oil and natural gas.

The temperature, pressure, and compaction of sediments increase at greater depths.

The large layers of sedimentary rock traps the natural gas and prevents it from rising to the surface. Although the areas where the gas is trapped are referred to as pools, natural gas molecules are actually held in small holes and cracks throughout the rock formation.

Geologists use sophisticated technology to help locate potential pools of natural gas to drill a well to extract gas. However, due to the complexity of locating natural gas trapped many hundreds of meters, and sometimes kilometers, below the surface, the exploration process is not always successful.

Conventional versus Unconventional Oil and Gas

Conventional resources are concentrations of natural gas that occur in discrete accumulations or pools. Rock formations hosting these pools typically have high porosity and permeability and are found below impermeable rock formations, such as shales or salts. These impervious layers form barriers to hydrocarbon migration resulting in oil and gas being trapped below them. Conventional oil and gas pools are developed using vertical or horizontal well bores and using minimal stimulation.

Conventional oil and gas pools fall into several categories based on the mechanism responsible for the trapping or pooling of the hydrocarbon:

- Structural traps whereby broad folds and/or faults lead to concentrations of hydrocarbons

- Dome-like structures related to diapiric rise of underlying

- Stratigraphic traps where a change in the rock type creates a barrier

- Multiple combinations of the above processes.

Prior to 2006, conventional oil and gas pools were the primary exploration targets in Western Canada.

Unconventional resources are oil or gas-bearing units, such as shales, where the permeability and porosity are so low that the resource cannot be extracted economically through a vertical well bore and instead requires a horizontal well bore followed by multistage hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) to achieve economic recovery and production.

Coalbed methane, tight gas, shale gas, and methane hydrates are all-natural gas found in different geological contexts. They are referred to as unconventional gas.

Currently, almost all wells being completed in the province are classified as unconventional. This is because the exploration industry can economically develop these widespread resources through the application of horizontal drilling and multi-stage hydraulic fracturing.

Shale Gas

Shale gas is natural gas produced from the fractures, pore spaces, and physical matrix of shales. Shales are the most commonly occurring type of sedimentary rock in northeast British Columbia.

By conservative estimates, northeast Br9itish Columbia has 1,200 Tcf of sha9le gas and 300 Tcf of tight gas in place. This potential production was the primary driver for record sales of petroleum and natural gas rights from 2006 to 2013.

Tight Gas

“Tight gas” lacks a formal definition, and the term’s usage varies considerably. It is generally described as “natural gas produced from reservoir rocks with such low permeability that hydraulic fracturing is necessary to produce the well at economic rates.”

Tight gas reservoirs occur throughout northeastern British Columbia in three distinct regions, based on structural and stratigraphic (rock layers) characteristics. Some of these regions are highlighted in ERROR! REFERENCE SOURCE NOT FOUND..

- Deep Basin — characterized by stacked Mesozoic clastic (dinosaur age) reservoirs, each regionally pervasive and gas-saturated, containing abnormally-pressured gas accumulations lacking downdip water contacts. The updip (northeastern) boundary of the Deep Basin is difficult to determine, as each reservoir unit has its own updip edge.

- Foothills — tight gas reservoirs of various ages and types produced where structural deformation creates extensive natural fracture systems. To the northeast, reservoir quality tends to be more conventional and fracturing plays a lesser role.

- Northern Plains — laterally extensive tight gas reservoirs produced where relatively subtle natural fractures can be exploited with horizontal drilling and advanced stimulation techniques. Only one unit, the Jean Marie platform carbonate near Fort Nelson, is an established producer.

Figure 7: NOTE while a good representation of the information, certain name places, such as the Queen Charlotte Islands are now officially known as “Haida Gwaii”.

Video 2: Unlocking Tightly Trapped Gas (5 minutes, 54 seconds)

![]()

Video 3: Lifecycle of an Onshore Well (5 minutes 52 seconds)

![]()

Learning Activity 2: Unconventional Opportunities

Instructions

This learning activity will help you identify some of the opportunities and challenges associated with unconventional natural gas extraction.

Watch Videos 2 and 3 and answer the following questions.

- What is the clearest part of these videos?

- From a jobs or careers perspective?

- From an environmental perspective?

- From a business perspective?

- From a community perspective?

- What is the most confusing part of these videos?

- From a jobs or careers perspective?

- From an environmental perspective?

- From a business perspective?

- From a community perspective?